Deep squats are defined as squatting past parallel, or past 90 degrees. The question is - is this safe to do? It’s a controversial question with a gray answer. In short, the answer is: it depends. If you are happy with that answer, thanks for stopping by. But if you want to fully understand why this simple question is more complicated than it seems, keep reading…

The muscles that activate during a squat

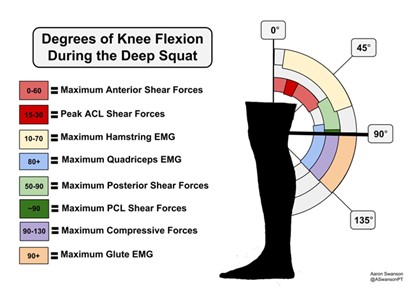

Different parts of the squat stress the joints and muscles in different ways. Some forces increase over the course of the squat and some maximize at specific points. Let’s single out the knee joint to better understand this.

There are two types of forces that act on the knee joint during the squat (Escamilla, 2001):

- Compressive – The quads muscle attaches to your knee cap (patella) via the quads tendon. The patella attaches to your leg bone (tibia) via the patellar tendon. As your knee bends, the quads and patella form a strap, creating compression behind the knee cap.

- Shear – The joints in our body move in two major ways, a roll and a glide. As you bend the knee, the joint spins in place (roll) but it also undergoes some translatory motion (glide). The gliding forces created during a squat stress different structures and vary with the depth.

Both types of stress are important for knee health and need to be considered when determining the safety of deep squatting. Exercise and physiotherapy is a biomechanical equation. It’s an equation of stress and we intelligently apply that stress to strengthen specific muscles and movements.

Unfortunately, it’s not a clear statement on whether squatting deep is good or bad - it simply changes the stress. The deeper you squat, the more compressive force you’ll have.

For those who like visuals, here is a great representation of the stresses placed on the knee at different degrees of the squat (Swanson, 2014):

Should you change the depth of your squat?

So is stress good? Yes! But is too much stress bad? Also yes… (why is it so complicated???). The deeper you go, the more stressful it is, and everyone has a different capacity for stress. Stressing muscles, tendons, and ligaments is how we strengthen them, but the specifics of how we navigate this is completely dependent on the individual and their injury history.

Changing the depth at which we squat changes the muscle activity. Electromyography (EMG) studies show higher quads and glutes activity the deeper you squat (Swanson, 2014). So do you have to squat deeper to get stronger? No, there are other ways to add stress including weight, speed, and even blood flow restriction (BFR) training, which creates the same type of stimulus to the muscle without increasing stress on the joint. Ultimately, the specificity of training is dependent on what you need to do and what you’re trying to get back to doing.

In summary

Is deep squatting evil? No. Does it place more stress on your joints? Yes.

The deeper you go, the more stress there is. There’s also more EMG activity in the quads and glute muscles, but there are other ways to increase EMG activity and gain that strength. Squatting is not bad for you, but the way you squat can be bad for you.

Simply stated, if you do not have adequate mobility in the ankle, knee, and hips, you will compensate elsewhere and cause more harm than good. The optimal squat depth is highly dependent on individual mobility and injury history. A depth that is appropriate for one person may not be for another, so don’t apply blanket rules to everyone. Instead, visit our sports and injury clinic to find the best way to move through your rehab.

References:

Escamilla RF. Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Jan; 33(1):127-41.

Swanson, A. “The Deep Squat.”, June 1, 2014. http://www.aaronswansonpt.com/the-deep-squat-part-1-the-good-the-bad-the-not-so-ugly/.